Bridges of Moscow. 2. Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge: bridge-city, iron bridge, bridge-brand

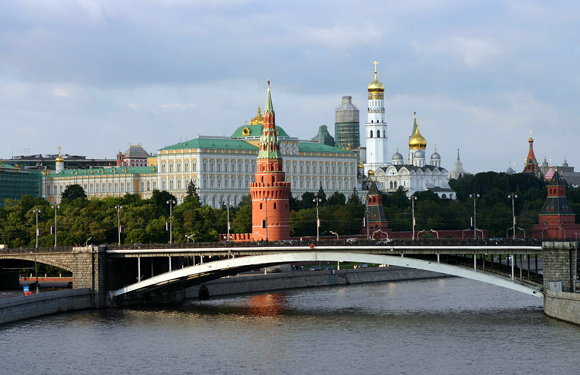

This is perhaps the most famous bridge in the capital. This is what can most often be seen in landscape photos of Moscow. Here you have the Kremlin, the Moscow River and, in fact, the Bolshoi Kamenny Bridge, raised high above the water. So to speak, “the brand of the capital”.

Just next to him, Gleb Zheglov and Volodya Sharapov, in the film “The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed,” met a soldier admiring the views of Moscow. It was after the war, which means they had already seen the bridge built in 1938.

Still from the film “The meeting place cannot be changed.” From left to right: Sharapov - soldier - Zheglov.

It is certainly convenient, since it has the best location in terms of traffic (its predecessors, invariably, would have caused traffic jams if they had been preserved). It is high enough and allows small ships to navigate the river without hindrance. The bridge offers one of the best views of the central part of the city, and it itself has a very beautiful design. However, the history of its predecessors is much more exciting.

So, the first crossing appeared at this place in ancient times and most likely passed through a ford. Its importance was constantly growing, since important roads and waterways converged here, and the settlement itself, which became part of the Suzdal principality, served as a strong military point on the border with several principalities (Smolensk, Novgorod, Ryazan and Seversky).

It is unknown when, but a floating bridge appeared here, which was a simple wooden structure made of boards laid on top of rafts that spanned almost 100 meters of the water surface. Such bridges were used everywhere and had many disadvantages. Firstly, they had to be separated and brought together during the passage of ships, which took a lot of time. Secondly, they could have suffered from a fire during the period of ice drift and freeze-up. So the bridge had to be built annually, after the ice disappeared and before it appeared. At a time when the crossing was removed and the ice was already beginning to break, getting to the other side was very difficult, dangerous, and sometimes simply impossible. Nevertheless, contemporaries praised the wooden “Moskvoretsky Bridges”. Foreigners also noted them. In the 17th century, Pavel of Aleppo, a traveler and church leader from the now infamous city of Aleppo, visited Moscow. He left the following notes: “The bridge near the Kremlin, opposite the gate of the second city wall, arouses great surprise: it is smooth, made of large wooden beams, fitted one to the other and tied with thick ropes of linden bark, the ends of which are attached to the towers and to the opposite riverbank. When the water rises, the bridge rises, because it is not supported by pillars, but consists of boards lying on the water, and when the water decreases, the bridge also lowers. When a ship with supplies for the palace arrives from the Kazan and Astrakhan regions... from Kolomna... to the bridges approved (on stilts), then its mast is lowered and the ship is carried under one of the spans; when they approach the said bridge, then one of the connected parts is freed from the ropes and taken away from the ship’s path, and when it passes to the Kremlin side, then that part (of the bridge) is again brought to its place. There are always many ships docked here, bringing all kinds of supplies to Moscow... On this bridge there are shops where brisk trade takes place; there is a lot of traffic on it; we go there for walks all the time... troops are constantly moving back and forth along it. All the city maids, servants and commoners come to this bridge to wash their clothes in the river, because the water here is high, level with the bridge.”

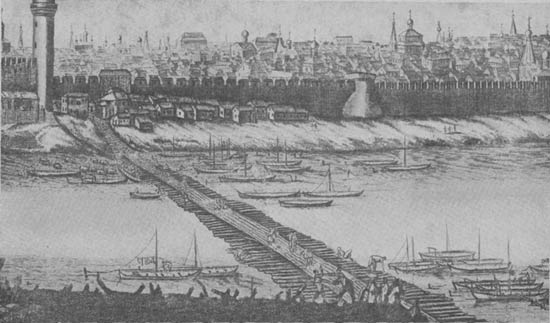

Moskvoretsky floating bridge. Engraving by Peter Picard. 17th century

Moskvoretsky floating bridge. Engraving by Peter Picard. 17th century

An engraving by Peter Picard, made in the 17th century and depicting a neighboring similar bridge on the Moscow River, will help you imagine what the floating bridge looked like.

The 17th century was very difficult for Moscow and many other lands of the state. Our country was experiencing the consequences of the Time of Troubles, the devastation of the land by the Poles, and frequent changes of rulers. Military settlements grew, and the artisan people also revived after a long period of chaos. There is a need to firmly connect the banks of the Moscow River with a stone bridge. Only in Moscow itself there was no experience in such construction, except for two small brick bridges built back in the 16th century, so they turned to a foreign specialist. In 1634, a “ward master” from Strasbourg, Christler, was invited. He came not alone, but with his nephew and many necessary tools. Based on their calculations, Russian craftsmen completed a wooden model, and foreigners prepared all the necessary calculations, which was presented in the Ambassadorial Order. However, the construction costs were not a joke, and the Duma clerk Grigory Lvov and stone mason Stepan Kudryavtsev, who carried out the examination, had to be convinced of their feasibility. The craftsmen guaranteed that the bridge would withstand “two arshins of ice” (about 1.5 meters), thanks to six stone “bulls” on powerful supports. They also assured the experts that “The vaults will be made thick and solid, and there will be no damage from the great burden.” The width of the bridge allowed troops and artillery to pass through. And on the Kremlin side, the structure was supposed to be connected to a powerful bridgehead fortification, which would make it possible to protect the approaches to the “heart” of Moscow. The project was presented to the Tsar, Mikhail Fedorovich, and was finally approved.

Almost immediately they began to prepare the necessary material. Unfortunately, the first royal Romanov did not manage to go down in history as the builder of the “miracle bridge,” since he died in 1645. By sad coincidence, Johann Christler followed the customer a year later. But the grandiose undertaking was postponed for many years.

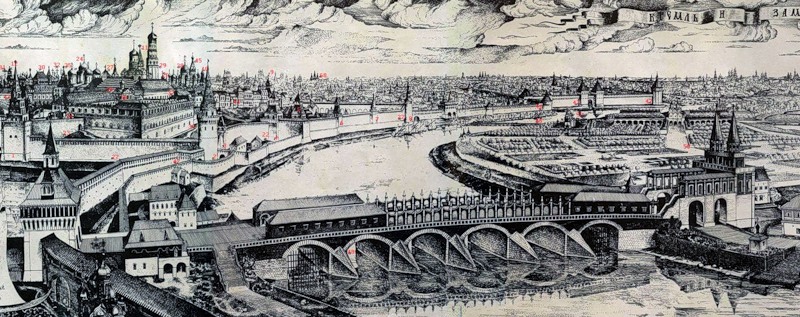

They returned to the project only in the 80s of the 17th century and completed the construction of the bridge for 5 years. The work was carried out under the guidance of a Russian master, and a monk at that. In the 90s, the bridge was completed and received the name All Saints, after the gates of the White City, to which it approached. (On a modern map of Moscow, this is the exit to the Moscow River on Lenivka Street, near the Kremlin). The opposite, Zamoskvoretskaya side ended with a tower representing a bridgehead fortification. All Saints Bridge at the end of the 17th century.

All Saints Bridge at the end of the 17th century. Drawing by Apollinary Vasnetsov.

The total length of the bridge was 140 meters, and the width was 22. This is approximately 3 times wider than the medieval streets of the center of Moscow. With such dimensions, the bridge has turned into a separate city, which is now even difficult to imagine! Wooden shops and stone chambers were built on it, where there were located: a beer yard, a Tavern office and a prison, trading in various goods. Above all this towered the “upper walkways”, used for the cultural drinking of low-alcohol drinks. Below there were glaciers to preserve goods. At the top there is a shopping, business and entertainment center for a decent public. People came here to admire the views of the city and entertainment, such as fist fights, which took place on the ice and watched with delight the ice drift from the safe height of the bridge.

In 1697, on the occasion of the capture of the Azov fortress, young Peter I, through this bridge and the Triumphal Gate located there, at the head of his troops entered the Kremlin. In addition, religious processions to the Donskoy Monastery from the Assumption Cathedral took place annually across the bridge.

The All Saints Bridge had another interesting feature: between the supports the river was blocked with a dam and a mill was built. Which, unfortunately, marked the beginning of its destruction due to the increased load. In addition, some researchers are inclined to believe that our builders were unable to comply with all the construction technologies conceived by Christler due to lack of experience, which also weakened the construction and, by the way, greatly increased the estimate. The bridge turned out to be very expensive and even became part of the popular saying at that time: “More expensive than the Stone Bridge.”

Surprisingly, only Anna Ioannovna, in 1731, took care of the safety of the bridge and its appearance, ordering the dismantling of the dams, flour mills and part of the shops. However, the bridge continued to collapse. Unfortunately, after losing its luster and splendor, the bridge fell into disrepute. Under its spans, a thief formed a den with the logical name “Under the Stone Bridge.” The most famous character there was Vanka-Cain, at the initial stage of his grandiose career, a thief, robber and, part-time, informant for the Detective Order. True, he organized his service in such a way that the entire Moscow police were in his service, and by this time he had already moved from under the bridge to one of the best mansions. However, the so-called “pechurs” - pits dug under the spans of the bridge, were replenished with new criminal elements, under the patronage of Vanka-Cain. By the way, this is where the thieves’ expression “ends in the water” came from, since those robbed were often simply thrown into the Moscow River near the Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge. The matter was raised on such a scale that it was necessary to send people from St. Petersburg, who were not involved in these matters, to restore order. According to evidence from that time, Moscow residents were afraid to spend the night at home, realizing that neither a wall nor a castle would save them. After each night, people were found killed and robbed in the city, and each morning began with the identification of the victims. This dark time ended only in the 50s of the 18th century with the defeat of the gangs and Vanka-Cain’s exile to hard labor.

In the 60s of the 18th century, the bridge was reconstructed under the leadership of Dmitry Vasilyevich Ukhtomsky, who is considered the founder of the Russian architectural Moscow school, which had the features of a magnificent baroque, while maintaining the national flavor. However, in this case, the famous architect did not rebuild the bridge, but only simplified its design by dismantling the six-gate tower and removing some of the benches to remove excess load. I did not come across any documents indicating that the supports were strengthened, but it is possible that the bridge stood for the next 20 years precisely because of these works. During that period, it was remembered as the last road of Pugachev, who was led to execution across the Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge to Bolotnaya Square, located one block beyond the Moscow River, in 1775.

And in 1783, the collapse of 3 arches occurred. A fisherman who was under the bridge, a washerwoman who was washing clothes, and 2 other people who were nearby died. To carry out restoration work, they dug the Vodootvodny Canal, because of which a long and narrow curved island, like a piece of Krakow sausage, appeared in the very center of the city, with the name Bolotny, which included the same Bolotnaya Square.

The next repair made it possible to extend the life of the decrepit Stone Bridge by several decades. Thus, he witnessed the fire in Moscow in 1812. The Napoleonic army retreated over its stones from the devastated city, and then, for a long time, building materials were transported to restore the burned center. It became very old and weak, constantly in need of repair, but when in 1859 the decision was made to demolish the Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge, most Muscovites perceived it as a sad loss. “How much effort and dedication it took to break this two-century-old monument! The very difficulty of breaking it proved the strength of its masonry and the goodness of the material, of which only one part was enough to build a huge house. Moscow residents gathered with curiosity and regret to look at the destruction of this bridge, which had long been revered as one of the wonders not only of our ancient capital, but of all of Russia in general,” wrote Snegirev, one of the eyewitnesses.

The bridge was broken, dismantled and even exploded with gunpowder charges until the place was completely cleared. And yet, the memory of him was preserved, at least in urban legends. Firstly, there is still a house in Moscow located at Mokhovaya Street, building 7, which, according to local residents, was built from the wreckage of the Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge. The reason for this was a note in the newspaper “Moskovskie Provincial Gazette” dated 1859. It said: “The merchant Skvortsov built a large apartment building on the corner of Mokhovaya from the purchased old material left over from the demolition with the addition of new ones, according to the design of the architect Nikolsky. The facade of this building is quite beautiful, there are good shops below; on the upper floors there are apartments of various sizes.” I could not find documentary evidence that the debris was part of the bridge. However, Moscow local historians, in their works, often adhere to this version.

The house, by the way, was rebuilt at the end of the 19th century according to the design of a St. Petersburg architect in the “Northern Art Nouveau” style. Its author, Vasily Vasilyevich Shaub, did a lot to develop this direction in architecture and created many different buildings that can now be seen on Vasilievsky Island and the Petrograd Side in St. Petersburg.

Secondly, many researchers believe that during the construction of the Dvortsovy, and now Lefortovo, bridge, the supports were made according to the model of the Bolshoi Kamenny. So it is considered a monument to this legendary building.

And recently, they began creating a graphic reconstruction of the Kremlin at the beginning of the 18th century. So now you can see what the Bolshoi Kamenny Bridge and the Kremlin looked like several centuries ago.

What can I say! Even with the construction of a new, metal bridge, the name “Bolshoi Kamenny” was retained behind it. It was designed by engineer Colonel Tannenberg. The new design had two stone supports with far protruding ice-cuts, on which cast-iron spans rested. Despite the fact that this was the first metal bridge in Moscow, it did not arouse any interest or delight among local residents and they got rid of it quite quickly, especially since there was a suitable reason. At the beginning of the 20th century, it greatly complicated the transport situation in the very center.

Big Stone Bridge (metal). XIX century. A Moscow joke from that time told about an unlucky official who looked in surprise at the huge protrusions of the supports and, finding out that they were ice cutters, said indignantly: “What if the ice comes from the other side?!”

In 1921, the Soviet authorities already announced a competition for the design of a new bridge. And only on the second attempt an option appeared that satisfied the commission. It was built in 1938, slightly moved downstream to Borovtskaya Square. The upper surface of the bridge is straight, it is supported by an arched metal structure resting on two stone shore supports. At the top there is a metal fence decorated with the Soviet coats of arms of Moscow flanked by banners with ears of corn on each side. The design turned out to be, frankly, unpretentious. But the main thing about it is that its shape and height block the view only of the Kremlin walls and at the same time emphasize its high location, serving as a kind of pedestal for the Kremlin towers and the Cathedral of Christ the Savior. At the same time, the Bolshoi Kamenny Bridge is one of the best observation platforms in the city. Engineer N. Ya. Kalmykov, in company with the architects: Vladimir Alekseevich Shchuko and Vladimir Georgievich Gelfreich (authors of the Smolny propylae), Mikhail Adolfovich Minkus, “stepping on the throat of his own song,” made the simplest bridge, poorly remembered, which recedes into the background, allowing you to see the main thing - a magnificent panorama of the banks of the Moscow River, which has preserved a large number of the most recognizable sights of the capital.