Konstantinovo, Yesenin Museum

If Pushkin is a world poet, then, undoubtedly, Yesenin is the most Russian poet of our era! How and where this poetry originated, where Sergei Yesenin first saw the fields, rivers and forests that inspired him to write such poems - you can find out by visiting the village of Konstantinovo on the banks of the Oka River.

Konstantinovo is a village in the Rybnovsky district of the Ryazan region. Located on the picturesque high right bank of the Oka, 43 kilometers northwest of Ryazan.

Konstantinovo is famous for the fact that the Russian poet Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin was born here on October 3, 1895 (new style). The poet spent his childhood and youth in Konstantinov. In the central part of the village there is the State Museum-Reserve of S. A. Yesenin.

Museum of the Zemstvo School in Konstantinovo

The history of the village of Konstantinovo goes back about 400 years. The first mention of it dates back to 1619; the village was then the property of the royal family. A few decades later it was granted to Myshetsky and Volkonsky.

Most of the village came to be owned by Yakov Myshetsky, who gave it as a dowry to his daughter Natalya when she married Kirill Alekseevich Naryshkin.

In 1728, the son of Kirill Alekseevich, Semyon Kirillovich Naryshkin, became the owner of Konstantinov. He received an excellent European education and served in the diplomatic service. Having no direct descendants, in 1775 he bequeathed Konstantinovo to his nephew Alexander Mikhailovich Golitsyn.

In 1779, at the expense of Golitsyn, a stone temple of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God was erected. In 1808, the estate was transferred to an illegitimate daughter, Ekaterina Alexandrovna, in her marriage to Dolgorukova.

According to her will, in 1843 her nephews Alexander Dmitrievich and Vladimir Dmitrievich Olsufiev became the owners of the village. After 2 years, they divided their aunt’s inheritance, and the eldest of the brothers, Alexander Dmitrievich, began to individually manage the estate. His son, Vladimir Aleksandrovich Olsufiev (1829-1867), took over the inheritance in 1853.

A significant event in the life of the peasants of the village of Konstantinovo was the manifesto of 1861, when they received personal freedom. At this time, 680 revision souls, which is exactly how many were listed according to the “revision tales” of the village of Konstantinovo, received 1,400 dessiatinas 740 fathoms of land into their ownership. For the ransom of which they paid 72,945 rubles.

The village was in the possession of the Olsufievs until 1879, when it came into the possession of the Kupriyanov merchants from the city of Bogoroditsk - Sergei, Alexander and Nikolai Grigorievich.

The eldest of the brothers, Sergei (1843? - 1923), built a zemstvo school and did a lot to educate peasant children.

In 1897, the owner of the house and estate became the Moscow millionaire, owner of apartment buildings on the Khitrov market, “hereditary honorary citizen of Moscow” Ivan Petrovich Kulakov.

Kulakov built a new school building and decorated the temple with a wooden oak iconostasis. According to the order of the Bishop of Ryazan and Zaraisk Nikodim (Bokov), he was buried in the church fence. After the death of her father in 1911, Lidia Ivanovna, married to Kashina, became the owner. She continued her parent's charitable activities.

Since 1917, a new historical period began in the life of the village of Konstantinovo.

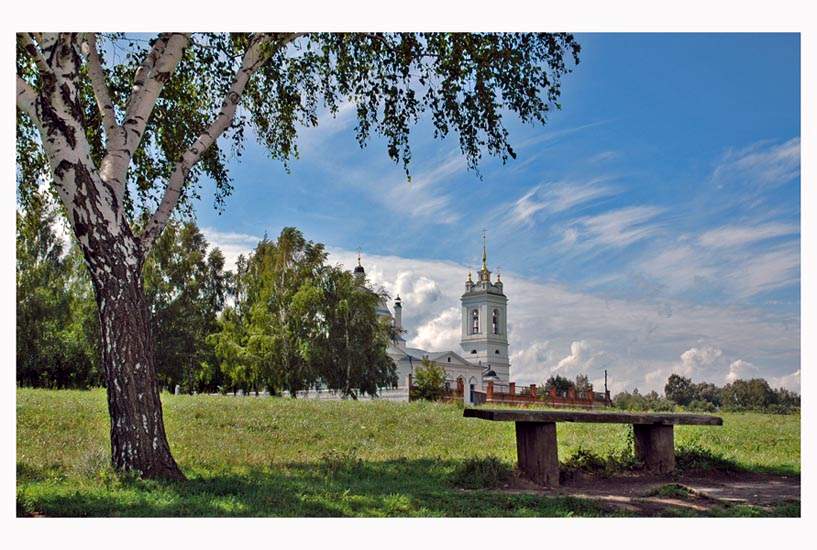

Temple of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God.

Rybnovsky district, Konstantinovo village.

At the expense of Alexander Mikhailovich Golitsyn, the owner of the village, a stone church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God was erected in 1779.

“The stone church of the village of Konstantinova has existed since 1779. Inside the church is decorated with paintings with beautiful ornaments and gold. ...The church was decorated through the efforts of the priest Fr. Smirnov and the zeal of a parishioner, the Moscow merchant Kupriyanov, who spared no expense in beautifying the church. The priest, Fr., also spent a lot of his money. Smirnov, who, after Kupriyanov’s death, had to pay the bills presented by the church’s creditors.”

Ryazan Diocesan Gazette. 1900.

“Our Konstantinovo was a quiet, clean, green village. The main decoration was the church standing in the center. The white rectangular bell tower, ending with five crosses - four in the corners and a fifth, higher, in the middle, dome, painted green, gave it the appearance of some amazing lightness and harmony.

In the openings of the bell tower one can see the bells: large, medium and four small.

...Behind the church on a high steep mountain is an old cemetery.

...The whole life of the village was closely connected with the church and the ringing of bells.”

Sergei Yesenin reads poetry to his mother

MUSEUM-RESERVE OF SERGEY YESENIN

History of the museum

The Ryazan land, poeticized by the genius of S.A. Yesenin, remembers its illustrious fellow countryman actively and gratefully. In his homeland, in the village of Konstantinov, the State Museum-Reserve S.A. Yesenina carefully preserves the memory of the poet and receives many admirers of his talent. For many years now, thousands of people of different ages and professions have been sailing, coming, coming to Konstantinovo to be imbued with the spirit of Yesenin’s poetry, to bow to the memory of the great artist.

Yesenin's poetry breathes the smell of native fields. It is filled with great love for the land on which the poet was born, for the people from which he came.

Favorite region. I dream about my heart

Stacks of sun in the waters of the bosom,

I would like to get lost

In your hundred-ringing greens.

Alas, the work of S.A. Yesenin did not immediately appear before readers as the work of a great poet. But that is the secret of his immortality. And the more a true poet leaves us as a living person, the closer and more fully he appears before us as a master of genius... (“Great things are seen at a distance”).

On January 1, 1926, an organizational meeting was held at the Herzen House to perpetuate the memory of S. Yesenin. It was proposed, in particular, to establish a hut-reading room named after S.A. in the poet’s native village. Yesenina.

With the same proposal, the Union of Soviet Writers of the USSR addressed the secretary of the Ryazan Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) comrade. A.I. Marfin. In a letter dated December 4, 1947, marked “Secret”, which is stored in the Party Archive of the Ryazan Region, we read: “Having considered the request of the mother of the late poet S.A. Yesenina T.F. Yesenina about the state acquisition of Yesenin’s house in the village of Konstantinovo, Rybnovsky district, Ryazan region for the organization of a museum in it, the Union of Soviet Writers of the USSR considers it possible to contact you with the following proposal: The Ryazan Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (b) instructs the relevant local organizations to allocate funds for the acquisition at T.F.'s house Yesenina in order to organize a hut-reading room in the village of Konstantinov with an exhibition corner dedicated to the work of the poet.

The Union of Soviet Writers takes over the patronage of this hut-reading room, the delivery of literature and materials for the exhibition. To maintain the reading hut and organize the exhibition, SSP considers it possible to attract the sister of the late poet E.A. Yesenin, with whom there is a corresponding agreement.” The letter was signed by the General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Writers A. Fadeev.

The first literary Yesenin exhibition on the terrace of L. Kashina’s house was organized by a delegation of the All-Russian Union of Writers headed by D.D. Blagim and V.L. Lvov-Rogachevsky, who arrived in Konstantinovo on July 5, 1926. A general meeting took place. On the veranda of the former manor house there was a presidium, whose members were the entire Yesenin family, representatives of the writers' delegation, the Village Council, and provincial organizations. Above their heads is unfurled the red banner of the All-Russian Union of Writers, which was donated to the village of Konstantinov (now it is kept in the funds of the State Museum of S.A. Yesenin). Moscow guests organized an exhibition of brought literature in a small hall of the Kashinsky house on the first floor. 1000 books added to the rural library

Since 1955, in Yesenin’s parental house, where the rural library worked, an exhibition on the topic “The Life and Work of Yesenin” was placed.

When the propaganda of S.A.’s creativity Yesenin was studied in the village library, then many fans of the poet came to the village. In the summer of 1964, more than 10 thousand people visited the poet’s house, although the museum was not yet open and records were kept extremely irregularly. Many of them left their reviews about visiting Yesenin’s homeland. These were not simple notes, but frank declarations of love for the poet and a request to open a museum.

By decision of the Ministry of Culture of the RSFSR, on the occasion of the memorable date, the 70th anniversary of the birth of S.A. Yesenin, a memorial museum was opened in the poet’s homeland, where he lived with his parents and sisters. The house-museum of S.A. Yesenin was initially a branch of the Ryazan Regional Museum of Local Lore. In the entryway of the memorial museum of S. A. Yesenin, a literary exhibition dedicated to the life and work of S. Yesenin was placed. It was made on the basis of the scientific and exhibition development of N. Khomchuk, an employee of the Pushkin House. Various stands reflected the complex life and creative path of the poet in photographs and documents.

Yesenins house-museum

In the hallway there is a poet's corner. By the window there is a wooden bed with a blanket made of colorful rags. Nearby is a chest containing books by favorite writers. On a hanger by the bed is his mother's fur coat, which the son called shushun. (“Don’t go out on the road so often in an old-fashioned, shabby shushun”). There are family photographs on the walls. The “Letter of Commendation” attracts attention: “This was given to the student of the Konstantinovsky rural school of the Ryazan district, Sergei Aleksandrovich Yesenin, for the very good successes and excellent behavior shown by him during the 1908/9 academic year.”

Everything in the house is as it was during the poet’s lifetime. His sisters took care of this, carefully preserving books, furniture, and utensils for many years. With their help, the atmosphere of everyday life of that time was recreated when the poet came to his home and composed tender poems:

“Our room, although small,

but clean. I am with myself at my leisure...

This evening my whole life is sweet to me,

like a pleasant memory of a friend.”

The poet’s sisters are an unforgettable part of Yesenin’s life for us. The role of these two women in the organization of the museum is truly invaluable. They provided information that was extremely valuable in quantity and detail related to the situation and life of the Yesenins. Everyone who loves S. Yesenin, bit by bit, like jewelry, collects and stores everything that is connected with the name of a dear person, especially if it is from first-hand knowledge, from a source of facts. The first director of the museum V.I. Astakhov constantly emphasized this, as well as the fact that the creation of the museum in a relatively short period of time became possible thanks to the selfless help of hundreds and hundreds of different people. The State Literary Museum donated many valuable exhibits - a rare portrait of the poet, first editions of his books, posters from the 20s. Employees directly participated in the development of thematic and exhibition plans of the museum, including the long-term one.

More and more people in love with Yesenin’s poetry from different places in our country and from abroad began to come to worship this corner, which raised the famous Russian poet. This circumstance created great difficulties for museum workers in serving visitors.

It was decided to allocate the former landowner's house of the Kashins for the Yesenin literary museum. Somewhat away from my parents' house there is a two-story mansion with a mezzanine. The building is notable for the fact that it is almost the only old house preserved in the village. The poet visited the owner of this house, L. Kashina, who to some extent was the prototype of A. Snegina in the poem of the same name. Since 1969, a literary museum has been located there, with an exhibition dedicated to the life and work of the poet. In the halls are S. Yesenin's manuscripts, revealing his creative laboratory. Documents, books... They trace the bright path of the Russian singer.

In 1984, the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR decided to create the State Museum-Reserve of S.A. on the basis of the existing literary and memorial museum in the village of Konstantinov and memorial sites in the city of Spas-Klepiki. Yesenina. Museum workers, architects, engineers, landscape architects, literary scholars, and foresters worked on its creation. On March 7, 1984, our museum received the status of the State Museum-Reserve of S.A. Yesenina. “Museum-reserve. These two words combine the fate of a person who glorified the Fatherland and the fate of the place itself, which is inextricably linked with the life of this person,” believed S. Geichenko. Love for his native land always inspired S. Yesenin and gave him creative strength.

Currently, the Museum-Reserve of S.A. Yesenin is a historically established complex of memorial buildings, which includes, in addition to the parents’ estate, the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, a chapel in honor of the Holy Spirit, the Konstantinovsky Zemstvo School and the estate of the last landowner of the village, Konstantinov L.I. Kashina, Spas-Klepikovsky second-grade teacher's school in the Spas-Klepikovsky department of the museum.

Undoubtedly, the most important component of the museum complex is the unique nature, which forced the poet to “pour out his whole soul into words.” The village of Konstantinovo is located on the high bank of the Oka. Below is a river, beyond which stretch magnificent floodplain meadows. Only after being here, you become convinced how closely the poetry of S.A. is connected. Yesenin with his native village.

Next to the Yesenins’ house there is a wooden zemstvo elementary school, restored for the 100th anniversary of Yesenin’s birth, from which Sergei graduated with a certificate of merit. The exhibition created there talks about the role of zemstvo schools in the education and upbringing of peasant children. The memorial classroom displays a slate tablet used by Sergei Yesenin, photographs of his first teachers, and textbooks.

The decoration of the village is the Kazan Church - an architectural monument of the 18th century. “The servant of God, the named son Sergius” was baptized in it. Priest I.Ya. Smirnov facilitated the admission of 12-year-old Sergei to the Spas-Klepikovskaya school, where a department of the museum-reserve was opened.

In 1995, after restoration work, the estate house of L. Kashina appeared in a new capacity as a museum of the poem “Anna Snegina.” The cozy atmosphere of the house transports visitors to the time when the poet visited it. In the exhibition you can see interesting memorial items, numerous photographs donated to the museum by the son of L.I. Kashina Yu.N. Kashin.

The literary museum displays unique exhibits: lifetime editions of the poet and his contemporaries, the book “Radunitsa” with the author’s first autograph, the table at which S.A. worked. Yesenin in the Caucasus, his death mask, personal belongings...

The museum exhibition at the Spas-Klepikovskaya school, from which Sergei graduated in 1912, tells, in particular, about the high humanistic traditions of Russian teaching, about the search for the spiritual path of youth, about the formation of the creative personality of the future poet. Today the State Museum-Reserve S.A. Yesenin is one of the largest museum complexes in the country.

Museum structure

Director:

Ioganson Boris Igorevich

tel.: (4912) 42-81-96

Email: [email protected]

Address:

391103, p. Konstantinovo, Rybnovsky district, Ryazan region.

Phones: (4912) 42-81-96; (49137) 33-2-96.

Fax: (4912) 42-81-96

Email: [email protected]

Official website: www.museum-esenin.ru

Museum opening hours

Memorial estate of parents of S.A. Yesenin, House of Priest I.Ya. Smirnova, Zemstvo School, Museum of the Poem “Anna Snegina” and the Literary Exhibition are open from 10:00 to 18:00, closed on Monday.

Saturday and Sunday - from 10:00 to 18:00.

Tickets are sold at the box office from 10:00 to 17:10.

HOW TO GET TO KONSTANTINOVO, WHERE IT IS LOCATED

From Moscow:

From the Kazansky railway station by the branded train "Express" Moscow-Ryazan or el. by train Moscow-Ryazan to the station. Rybnoye, then by bus or minibus (No. 132).

From the Vykhino bus station by bus to Ryazan (No. 960).

Those who want to get there on their own can use the Google map.

From Ryazan:

From the bus station "Central" to the village. Konstantinovo

Ryazan - Rybnoye - Konstantinovo - Vakino - 6:10; 9:40; 13:40; 18:35 (daily)

* Buses arrive at the stop in Rybnoye 20-25 minutes after departure from the Central bus station and from the bus stop. Konstantinovo in the direction of Ryazan

From Rybnoye

Rybnoye - Aksenovo - Konstantinovo - 8:00; 12:00; 16:30 (daily)

From the village Konstantinov in Ryazan (via Rybnoye):

Bus: 7:25; 11:00; 15:00; 20:00 (daily)

From the village Konstantinov in Rybnoye

Minibus taxi (gazelle): 8:30, 12:30, 17:00 (daily)

WHERE TO STAY

Guest house of the State Museum-Reserve S.A. Yesenin is located in the center of the village of Konstantinova, not far from the memorial estate of S.A.’s parents. Yesenina.

At your service: three comfortable rooms. The cozy guest house has a shower, a bathroom, and a small kitchen equipped with everything necessary for cooking. Read more here...

Tel.: 8-920-950-51-67,

8(49137) 33-2-45

The recreation center "Barskie Zaby" is located in a picturesque place near the village. Onboard.

At your service: comfortable wooden log cottages for year-round use. All rooms are double rooms with private facilities. The houses have an equipped kitchen, a living room with TV. Three meals a day in the traditions of Russian cuisine. Services: accommodation, horseback riding and hiking, sauna, hound and falconry hunting, fishing, family and children's programs.

Tel.: 8-910-901-36-62

8-920-963-27-77

Recreation center "Oka", located on the high bank of the Oka near the village. Ivanchino.

At your service: 13 double rooms, a two-room suite. The rooms have a bathroom and shower. In addition, there are separate summer cottages - four-bed rooms with a bathroom and washbasin. Infrastructure and services: cafe-bar, bathhouse, snow-tubing track for skiing on inflatable tubes, skiing and skating in winter, cycling in summer, rental of sports equipment, sports grounds, children's areas, outdoor heated swimming pool, picturesque forest, walks along bank of the Oka.

Tel.: 8-961-132-47-23

2-961-132-47-24

Children's Orthodox camp "Derzhavny", located in a beautiful place on the banks of the Oka River near the village. Aksyonovo.

Unique views, walks, swimming in the river, food, convenient access. There are cottages for accommodation.

Tel.: 8-910-630-08-84

8-960-572-71-01

Guest house "Monastery Road", located in the village of Poshchupov, in close proximity to the St. John the Theological Monastery and the famous Holy Spring.

It offers visitors: cozy rooms, a cordial atmosphere, delicious homemade food, reasonable prices.

Tel.: 8-960-572-94-13.

Travel time from all objects to the S.A. Museum-Reserve. Yesenina

does not exceed 15 - 20 minutes.

in the Yesenins' house

YESENINS' ESTATE

Yesenin Estate

In the center of the village of Konstantinova, opposite the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, the Yesenin estate is located. Here, in 1871, the poet’s grandfather Nikita Osipovich Yesenin built a house where Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin was born on September 21 (October 3 - according to the new style) 1895. Over time, the dilapidated grandfather's house was demolished, and in its place in 1909 a new, smaller one was built. It is with him that Yesenin’s poetic image of the “golden log hut” is associated. In 1965, a museum of the famous Russian poet was opened in this simple village hut. Over time, a whole complex appeared in Konstantinov - the State Museum-Reserve of S.A. Yesenina. But its heart still remains the “low house” of the Yesenins, restored in 2000.

The exposition of the house takes us back to the 20s, when, being a famous poet throughout Russia, Sergei Yesenin came to his parents’ house to rest his tormented soul here.

A spacious entryway leads to the warm part of the house, where among the peasant utensils and tools, the sickle and half-braid of Tatyana Fedorovna Yesenina, the poet’s mother, stand out.

As soon as you enter the residential part of the house, you cannot help but notice the small kitchen with a snow-white Russian stove and household items. On the table there is a bucket “grandfather’s” samovar - a witness to many tea parties in the Yesenin family.

Opposite the kitchen is a hallway with a Dutch oven. The poet slept on a wooden bed next to a hot stove when he came to his parents’ house in the cold season.

The largest and brightest room is the upper room. In the red corner are icons of Tatiana Fedorovna, her pectoral cross. On the wall next to the stove are family photographs and Sergei’s certificate of merit, which he received upon graduating from the zemstvo school. The “wooden clock” also counts down time, as if an oak table with a kerosene lamp under a green lampshade, by the light of which Sergei Yesenin often worked, is waiting for the poet.

From the upper room we find ourselves in the room of the poet's mother. Here are her clothes and the famous fur coat - “shushun”, in which Tatyana Fedorovna often went out onto the road and, peering into the distance, waited for her son.

Immediately behind the house there is a garden where cherries grow in abundance. Hidden in its depths was a temporary hut (restored in 2003), in which, after the fire of 1922, the Yesenins were forced to huddle. Nearby is an apple tree that miraculously survived the fire. Not far from the temporary hut there is a barn built back in 1913. During the poet’s summer visits, it turned into his bedroom and study. At the very end of the estate there is a restored barn (shed for drying sheaves).

In 1970, a park was laid out next to the Yesenins’ estate, where trees dear to the poet’s heart were planted: birches, maples, lilacs, lindens, rowan trees... On October 4, 2007, a bronze monument to Sergei Yesenin by the sculptor was installed in the park

A.A. Bichukova.

The Yesenin estate is never deserted: at any time of the year, fans of the poetry of S.A. Yesenin are eager to see the land that gave the world the great poet.

RADUNITSA

Song and instrumental ensemble "Radunitsa"

It is impossible to imagine Yesenin’s poetry without Russian song. “I was born with songs in a grass blanket...” the poet exclaims in one of the poems of the first poetry collection “Radunitsa”. In the very choice of the name, S. Yesenin emphasized the inextricable connection of his work with Russian folklore, with Russian folk song. The songs and tunes that sound in Yesenin’s native village have a unique flavor. Distinguished by the amazing beauty of the melodies, the brightness of the musical and poetic language, they were an inexhaustible source of inspiration for the poet. To collect, preserve this rich heritage, and introduce it to numerous admirers of S. Yesenin’s talent is the main task of the song and instrumental ensemble “Radunitsa”, created in 1983, the direction of the search for which organically coincided with the activities of the museum-reserve.

Each generation brings something new to folk art and, therefore, “Radunitsa”, along with traditional ones, also uses modern means of expression.

The ensemble performs songs based on poems by S. Yesenin, works by composers G. Ponomarenko, E. Popov, N. Kutuzov, Yu. Zatsarny, E. Derbenko, B. Rubashkin.

The ensemble "Radunitsa" visited many parts of our country and performed successfully in Spain, Bulgaria, and Germany. The team has repeatedly confirmed its professional skills at competitions for performers of Russian folk songs, becoming a diploma winner at the III All-Russian competition in 1985, and a laureate and winner of the main prize of the State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company at the I All-Russian television and radio competition “Voices of Russia” in 1990.

Mentions of songs, instruments, and folk rituals are often found in S. Yesenin’s poems. All his poetry became a song, permeated with tender love for his homeland, absorbing the soul of the Russian people. That is why folk melodies, once heard by the poet in his native land, and songs based on his poems are so dear to us. I would like to hope that all this will become dear to you, and the joy of meeting “Radunitsa” will remain in your heart for a long time.

MUSEUM OF THE POEM ANNA SNEGINA

Next to the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God is the estate of the last Konstantinovsky landowner Lydia Ivanovna Kashina. Sergei Yesenin first met the owner of the estate in the summer of 1916. At this time he was already the author of his first poetry collection, “Radunitsa”. Lydia Kashina became one of the prototypes for the main character of the poem “Anna Snegina”. Sergei Yesenin visited Kashina’s house more than once, since he had friendly relations with the hostess. In 1918, after the nationalization of the estate, the poet helped Lydia Ivanovna move to Moscow, and he himself stayed in her Moscow apartment. After the revolution, Kashina’s country house was used for the needs of the village, and in October 1969 a literary exhibition was opened there. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the poet’s birth in 1995, the museum’s exhibitions of one Yesenin poem, “Anna Snegina,” were located in the rooms of the house.

Museum exhibitions occupy the first floor of the “house with a mezzanine”. The exhibits tell us about the life of the Kashina family, its guests, and the poet’s fellow villagers. Manuscripts, photographs, and household items help to draw parallels between the inhabitants of the house and the heroes of the poem, telling about the life of the Constantinians during the years of the revolution. Among the exhibits are Lydia Ivanovna’s memorial grand piano, her miniature chest of drawers, a box and other items. Autographs of Sergei Yesenin’s poem “Anna Snegina” accompany museum visitors in almost every room.

From them one can trace the poet’s attitude to the First World War and the Revolution, the mood of the village residents in the “harsh, menacing years,” and the relationships of the heroes. The exhibition presents the first collection of poems by Sergei Yesenin “Radunitsa”, the poet’s personal belongings: inkwell, paperweight, ashtray, notebook cover, etc.

The mezzanine of the house houses temporary exhibitions from the museum's collections.

The Museum of the Poem “Anna Snegina”, through an introduction to the house where the poet visited, immerses the reader in the atmosphere of the events described in one of the best poems by Sergei Yesenin.

LITERARY EXHIBITION OF THE POET YESENIN

A literary exhibition telling about the life and work of S.A. Yesenin, is located in the building of the scientific and cultural center of the museum. It was opened in 1995 on the 100th anniversary of the poet’s birth. Here are objects, documents, manuscripts, photographs, letters, works of fine art that allow us to consistently present the stages of Sergei Yesenin’s formation as a poet and his complex life and creative path.

For ease of study, each period of the poet’s life is presented separately. With the help of exhibits, museum visitors can trace all stages of the fate of the great Russian poet from birth in 1895 to his mysterious death in 1925.

The effect of Sergei Yesenin’s presence in the exhibition is enhanced by memorial items: the cradle in which the mother rocked baby Sergei; wall panel from the Moscow apartment of A.N. Yesenin, the father of the poet; jacket, cane and top hat by Sergei Yesenin; the chest-cabinet of the poet, with whom he traveled abroad, etc. Yesenin’s lifetime publications are widely represented, among which special attention is paid to the poet’s first book of poems “Radunitsa”, autographs of works, letters, documents, books from the poet’s personal library.

A separate section is devoted to the fate of Sergei Yesenin’s works after his death and the difficult path of returning them to the general reader.

The literary exhibition helps visitors to the museum-reserve feel the poet’s blood connection with his native village, Sergei Aleksandrovich Yesenin’s devotion to his dear fields and meadows, since his love for his native Ryazan land gave him strength in the most difficult moments of his life.

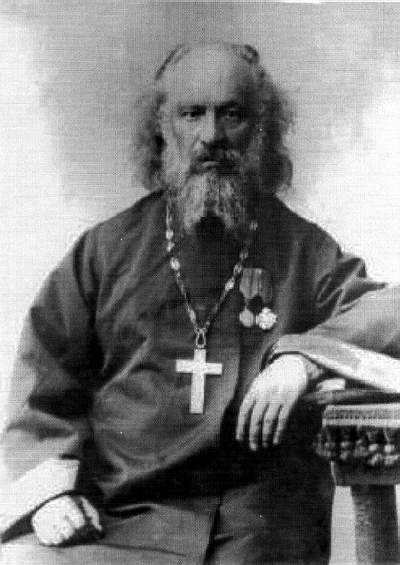

Priest's house I.Ya. Smirnova

On October 3, 2010, the house of priest John Smirnov was restored in the museum-reserve, since this man played a significant role in the fate of young Sergei Yesenin. It was this shepherd, respected by his fellow villagers, who married the poet’s parents, baptized Yesenin himself, to whom he gave the name in honor of St. Sergius of Radonezh, and taught the Law of God at the zemstvo school.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the house of Father John was the cultural center of Konstantinov. The surrounding clergy, rural intelligentsia, and student youth gathered at his place; Sergei Yesenin often visited there.

The priest's house now houses an exhibition dedicated to the life of Father John in Konstantinov, as well as to the acquaintances and friends of the poet from his youth.

The exhibition presents documents written by the hand of Father John: clergy registers, sheets from his diary. The priest had a good library, which young Sergei Yesenin also used. Liturgical books, as well as collected works of classics and publications subscribed to by Father John, are on display. Next to the icon corner is an interesting collection of Easter eggs and greeting cards. Musical instruments: harmonium, violin, guitar, as well as sheet music tell about the passion of young people from the priesthood for music and choral singing.

Many young people visited Father John’s house. Here Sergei Yesenin met young men and women, relatives and acquaintances of Father John. He became especially friends with Nikolai and Anna Sardanovsky and Maria Balzamova (photos of these young people are presented at the exhibition). The rural intelligentsia paid great attention to their costume, so ladies' and girls' dresses, men's shirts made in folk style arouse great interest among visitors to the exhibition.

It was Father John who was one of the first to note the young man’s talent, recommending Sergei to enter the Spas-Klepikovsky teacher’s school.

Autographs of early poems, first magazine publications, a greeting card that young Yesenin sent to his “dear father” from Moscow in 1913 - all this shows how loved the poet was by the rural shepherd.

The exhibition, located in the house of priest Ioann Smirnov, and the documentary film “The Poet and the Shepherd,” which can be viewed at the exhibition, allow us to better imagine the social circle of the young poet, in which his worldview developed, which was later reflected in the early work of Sergei Yesenin.

FROM THE BIOGRAPHY OF SERGEY YESENIN

“A magical strangeness occurred with Yesenin’s posthumous fate,” he wrote in the early 50s. last century poet Georgy Ivanov. “He has been dead for a quarter of a century, but everything connected with him, as if excluded from the general law of dying, pacification, oblivion, continues to live. Not only his poems live, but everything “Yesenin”, Yesenin “in general,” so to speak. Everything that worried him, tormented him, pleased him, everything that somehow came into contact with him still continues to breathe the reverent life of today.” (Ivanov G.V. Yesenin. - Sergei Yesenin in poetry and life (hereinafter - EZH). M., 1997. T. 4. P. 141). These words remain valid more than half a century later.

BIOGRAPHY

SPIRITUAL SOURCES

Sergei Aleksandrovich Yesenin was born on October 3, 1895 into a peasant family, in the village of Konstantinovo, Ryazan province. “There was nothing remarkable in our Konstantinov,” recalled the youngest of Yesenin’s sisters, Alexandra Alexandrovna: “It was a quiet, clean, green village. The main decoration was the church standing in the center of the village. Slender perennial birch trees with many rooks’ nests served as decoration for this beautiful and unique monument of Russian architecture. Acacias and elderberries grew along the church fence.

Behind the church, on a high and steep mountain, is the old cemetery of our great-grandfathers” (Yesenina A. A. This is all dear and close to me. - EJ. Book 4. P. 29). Yes, indeed - a typical Russian landscape. Modest, unobtrusive nature and necessarily a church, which fits so harmoniously into the surrounding landscape and spiritualizes it.

Nature and prayer are the first things that were imprinted in the soul of every Russian peasant, which accumulated from generation to generation and sometimes gave a surge in individual representatives of the family: saints, ascetics, composers of folk songs, and in the 19th century in poets such as Koltsov, Nikitin, Surikov, whose followers at the beginning of the 20th century were Drozhzhin and Klyuev. Yesenin himself was aware of his genetic continuity from the older “poets of the village.”

The inseparability of rural life and prayer, the feeling of all nature as a temple - and not an abstract temple, but an Orthodox one, with all its attributes, was clearly manifested in his early poetry.

The evening is smoky, the cat is dozing on the beam.

Someone prayed: “Lord Jesus.”

The dawns are blazing, the fogs are smoking,

There is a crimson curtain over the carved window.

Cobwebs curl from the golden thread.

Somewhere a mouse is scratching in a closed cage...

Near the forest clearing there are heaps of bread in the piles,

The spruce trees, like spears, pointed to the sky.

They filled with smoke under the dew of the grove...

Silence and power rest in the heart.

These poems were written by Sergei Yesenin at the age of 16-17 years. In this and a slightly later period, the metaphor of nature-Temple is one of the main techniques of his poetics.

“The black wood grouse is calling for the all-night vigil”; “the bells of the winds sing a dirge”, “in the wind’s good news there is a drunken spring”, “and the birches stand like large candles”, “in the firs there are the wings of a cherub”; “The schema-monk-wind with a careful step crushes the foliage along the ledges of the road and kisses the red sores of the invisible Christ on the rowan bush” - these examples are in dozens already on the first pages of Yesenin’s collected works.

In essence, this is a repetition and variation of one simple technique, but in order to write like this, you need to have a special vision of the world - and Yesenin undoubtedly had it - from nature, from God.

The version of Yesenin’s biography, which his relatives adhered to, definitely bears the stamp of the hagiographic canon. Mother, Tatyana Fedorovna Yesenina, whose memories of her son were recorded from an oral history many years after his death, said this: “There was a righteous man in our village, Father Ivan. He says to me: “Tatiana, your son is marked by God.” (ECJ, book 4 p. 5).

Priest, Fr. Ivan Smirnov, connected with the Yesenin family either by friendly or even family ties, appears in many memoirs about Yesenin, written by his relatives and fellow countrymen. He, indeed, was one of the first who saw the “spark of God” in the boy.

And yet, the further fate of the most famous peasant poet of Russia makes us recall the most “peasant” of the Gospel parables - the parable of the sower. “The sower went out to sow. And while he was sowing, it happened that some fell along the road, and birds came and devoured it. Some fell on a rocky place where there was not much earth, and soon sprang up because the earth was not deep; When the sun rose, it withered and, as if it had no root, withered away. Some fell among the thorns, and the thorns grew and choked the seed, and it did not bear fruit...” (Mark 4:3-7).

Unfortunately, speaking about Yesenin - not as a poet, but as a person - there is perhaps no need to continue further, because his case has already been described.

“I would gladly refuse many of my religious poems and poems,” Yesenin wrote in his last autobiography, 1925, “but they are of great importance as the poet’s path to the revolution” (Yesenin S.A. Complete Works. M. 1999 . T. 7. P. 20).

CHILDHOOD

Sergei Yesenin spent most of his childhood in the house of his maternal grandfather, Fyodor Andreevich Titov. The family life of his parents did not work out from the very beginning: either the mother returned to her parents, or the father went to work in Moscow, where he worked in a butcher shop. Their marriage, however, did not break up; after their son Sergei, their daughters, Ekaterina and Alexandra, were born with significant interruptions.

Yesenin himself spoke about his childhood in different ways. In his 1924 autobiography, he writes: “My first memories date back to the time when I was three or four years old. I remember a forest, a big ditch road. Grandmother goes to the Radovitsky Monastery, which is about 40 miles from us. I, grabbing her stick, can barely drag my legs from fatigue, and my grandmother keeps saying: “Go, go, little berry, God gives happiness.” Often blind men, wandering through the villages, gathered at our house and sang spiritual poems about a beautiful paradise, about Lazar, about Mikol and about the groom, a bright guest from an unknown city.<…>Grandfather sang me old songs, so drawn-out and mournful. On Saturdays and Sundays he told me the Bible and sacred history” (PSS. T. 7. P. 14).

From the 1925 autobiography, pious details disappear completely. However, in earlier notes Yesenin liked to emphasize that he had always been a mischief-maker, a brawler, and a ringleader.

He recalled how his unmarried uncles—“mischievous and desperate kids”—put him, three years old, on a horse without a saddle and let him gallop.

Or how the same “wise mentors” taught him to swim: they sailed a boat from the shore and threw him, like a puppy, into the water. Not without challenge and pleasure, Yesenin spoke about his childhood “freethinking” and “blasphemy”: “On Sundays they always sent me to mass and, to check that I was at mass, they gave me 4 kopecks. Two kopecks for the prosphora and two for the priest taking out the parts. I bought a prosphora and, instead of the priest, made three marks on it with a penknife, and for the other two kopecks I went to the cemetery to play piggyback with the guys” (PSS. T. 7. P. 9).

However, piety in the Titov-Yesenin family was largely external. With the exception of the grandmother, Natalia Evtikhievna Titova, the rest of the family did not differ in the depth of religiosity.

And this was not their individual “apostasy” - faith in the village weakened, just as it weakened throughout society. At the beginning of the 20th century, that “reasonable, good, eternal” began to emerge, which the Russian intelligentsia generously sowed in the countryside throughout the second half of the 19th century. However, already the first “shoots” showed that a mutant was growing: arrogance, insolence, shamelessness and, of course, ingratitude - it is not worth repeating what a “heartfelt thank you” the intelligentsia heard for the centuries-long work of teaching the peasants to read and write and treat diseases.

However, for people with a spiritual view of the world, the result was predictable. Outwardly, religious rituals were preserved, but in the mass they were just an outer shell. Yesenin’s mother, Tatyana Fedorovna, speaks about this directly, not at all regretting her “timeliness”: “Not to say that he was religious, but still I took him wherever he needed to go in his childhood. I taught it. We are old people, it was necessary. And now it’s a different time” (ESJ. Vol. 4, p. 6).

Nevertheless, there is another interesting detail in Yesenin’s biography: in childhood he was called “Seryozha the Monk”. The nickname had a completely everyday origin, and it was not even the future poet himself who was the reason for its appearance: it was inherited from his grandfather, who married very late by village standards (at 28 years old) and before his marriage managed to earn the nickname “monk” - but in life nothing doesn't happen completely by accident.

Both the relatively pious and hooligan past of Sergei Yesenin are confirmed in the memories of loved ones.

And besides, the thirst for learning awoke in him early. “Among the students, he was always distinguished by his abilities and was among the first students. When someone didn’t learn a lesson, the teacher left him without lunch to prepare his lessons, and entrusted Yesenin with carrying out the check - recalled his childhood friend, Klavdiy Vorontsov. “He ruled among the children even during non-school hours.

Not a single fight can happen without him, although he got hit twice as well. His words in verse: “there is always a hero among boys”, “and I muttered through a bloody mouth towards my frightened mother”, “a bully and a tomboy” - this is a reality that no one can deny. (VE. T. 1. P. 126).

The mother’s memoirs paint a completely different image: “He read a lot of things. And I felt sorry for him that he read a lot and got tired. I'll go put out his fire so he can lie down and sleep. But he didn't pay attention to it. He lit it again and read. He will finish reading until dawn and, without sleeping, will go to study again. He had such a greed for learning, and he wanted to know everything.

He read a lot, I don’t know how to say how much, but he was well read. I studied at my own rural school. Four classes. Received a certificate of merit. After his studies, we sent him to a seven-year school, which not everyone could get into at that time. It was only accessible to the master's children and priests, but not to the peasants. But since he studied well, the priest (the already mentioned Fr. Ivan Smirnov - T.A.) was an experienced person, saw that he had talent, and advised my father and me: “Let’s send him.” He studied there for three years, in the seven-year school.” (ECJ. Book 4. pp. 5-6).

The parents were very proud of the success of their first-born. The certificate of commendation that Sergei received upon graduating from primary school was even hung on the wall by his father, having removed all the portraits that had previously hung on it.

However, Yesenin himself spoke disparagingly about his childhood thirst for knowledge, which his mother recalled with such pride half a century later: “When I grew up, they really wanted to make me a rural teacher, and therefore they sent me to a closed church-teacher’s school, after graduating from which, at the age of sixteen , I had to enter the Moscow Teachers' Institute. Fortunately, this did not happen. I was so fed up with the methodology and didactics that I didn’t even want to listen” (PSS. p. 9).

Yesenin learned the strange tone of a spoiled papa and mama’s boy for a peasant son later. At the beginning of his career, he, apparently, was not alien to the desire to work in the pedagogical field. He also understood the vocation of a poet as serving people:

The poet who destroys enemies

Whose native truth is mother.

Who loves people like brothers,

And I’m ready to suffer for them.

He will do everything freely

What others couldn't.

He is a poet, a folk poet,

He is a poet of his native land.

The poem is dedicated to “My dearly beloved friend Grisha” - Grigory Panfilov, whom Yesenin met at the Spas-Klepikovskaya seven-year school and with whom he shared his most secret things. Grisha was seriously ill with tuberculosis and died in 1914. For Yesenin, this was a heavy loss: he lost a man who apparently had a great influence on him and encouraged him to follow the path of the “people's poet.”

Although these poems are still imperfect, naive and banal, they testify to the desire for self-sacrifice, for the heroic, prophetic path, to which Yesenin, apparently, really had a calling. In the fall of 1912, Sergei sent Grigory Panfilov from Moscow a “leaflet” - an oath given to him, “friend Grisha” and to himself: “Bless me, my friend, for noble work. I want to write “The Prophet” (a dramatic work - T.A.), in which I will brand the blind crowd, mired in vices, with shame.

If there are other thoughts stored in your soul, then I ask you, give them to me as for the necessary material. Show me which way to go so as not to blacken yourself in this sinful host. From now on I give you an oath, I will follow my “Poet”. Let humiliation, contempt and exile await me. I will be firm, as will my prophet, drinking a glass full of poison for the holy truth with the consciousness of a noble feat” (ESJ. Vol. 3. p. 13). These were the aspirations with which Sergei Yesenin entered adulthood, and which for some reason, having barely tasted this adult life, he very quickly lost.

Tatyana Fedorovna Yesenina narrated the circumstances of her son’s departure to Moscow in the same fairy-tale spirit: “When I finished the seven-year school, I came home (from Spas-Klepikov - T.A.). His father recalled him to Moscow, to his place. He went and did not disobey. He was sixteen years old. His father put him in his master's office. He didn’t like it right away” (ESJ. Vol. 4, p. 5). According to his mother, Sergei did not like the fact that the mistress beat the servants. And he left and got a job at Sytin’s printing house.

Next, Tatyana Fedorovna tells a fantastic episode of her son’s already idealized biography: supposedly the elderly publisher Sytin, as well as the young printing worker Sergei Yesenin, wrote poetry, and both simultaneously decided to start publishing, with Yesenin’s poems being published, and Sytin’s - no, which Sergei was very sad about, because he was offended for the rejected old man. Of course, such a legend about Yesenin as a strictly obedient son, a defender of the weak and oppressed, can only be accepted with a smile, but in connection with it, traits of Yesenin’s character are revealed that also cannot be ignored.

On the one hand, every legend has a certain amount of truth, and this positive characteristic of Yesenin should not be dismissed. On the other hand, a predisposition to myth-making says a lot about the myth-maker himself. A certain inclination towards showing off, apparently, was characteristic not only of Yesenin, but also of his relatives and fellow countrymen, and perhaps of the peasants in general (after all, it is no coincidence that Gorky did not like the peasantry as such for its “duplicity”).

An interesting detail is given in the memoirs of the younger sister, A. A. Yesenina: “As a rule, they ate well during haymaking. The housewife has a lot of trouble. You need to bake pancakes, fights, pies, and cook good cabbage soup. For mowing, as for a holiday, they stock up on eggs, lard, cottage cheese, buy meat or slaughter a lamb or calf. There are two reasons for good nutrition: firstly, the work is hard, and secondly, you have to dine in the meadows, in full view of everyone” (ESJ. Vol. 4. p. 32). The latter is also understandable: everyone wants to show that he and his family are “no worse than people.” Perhaps, if you look closely into your soul, it is not entirely commendable to appear better in public than within your family or alone with yourself, but, on the other hand, it is not bad if a person wants to conform to the healthy foundations of society. But if a person leaves his usual foundations and finds himself in a different environment, without having his own solid inner core, this desire to be “no worse than people” can have the most tragic consequences. This is what happened to Yesenin.

Once in the city, he very quickly made acquaintances among the revolutionaries. As soon as he became one of the employees of Sytin’s publishing house, he already signed some kind of “Collective letter of five groups of class-conscious workers in support of the Bolshevik faction in the State Duma.” What did this poetic young man with a keen sense of nature have in common with the “conscious workers”? And what could he understand about politics? But, obviously, he wanted to be “no worse than others” - both then, in the case of the letter, and then when he hastily married one of his colleagues at the printing house, Anna Izryadnova, in a civil marriage, and when in his letters he began to speak disparagingly about his parents : “My mother died morally for me a long time ago, and my father, I know, is near death” (Letter to M.P. Balzamova, 1912 - EJ. Vol. 3. P. 10). Manya Balzamova is another friend of her youth, a teacher in the future, a pure, thinking girl. He, it seems, opens his whole soul to her, and in letters to his friend Grisha cynically remarks that “he’s done with the nonsense with her,” and that he “threw a whole bunch of her letters into the closet.”

Already at the beginning of his Moscow life, he is tempted by the demon of suicide. “I don't know what to do with myself. Suppress all feelings? Kill melancholy in dissolute fun? Doing something so unpleasant to yourself? Either to live, or not to live? And it becomes so painfully painful that you can even risk your existence on earth and say to yourself so contemptuously: why do you need to live, you useless, weak and blind worm? What is your life? (Letter to M.P. Balzamova, 1912 - EJ. T. 3. P. 9).

Later, in a letter to the same Mana Balzamova, he makes the following confession: “My self is a disgrace to my personality. I was exhausted, broke and, one can already say with success, I buried or sold my soul to the devil - and all for talent. If I catch and possess the talent I have intended, then the most vile and insignificant person will have it - me. If I am a genius, then at the same time I will be a filthy person. This is not an epitaph yet.

1) I have no talent, I just ran after it.

2) Now I see that it’s difficult for me to reach heights - I don’t have enough meanness, although I’m not shy about choosing them. This means that I am an even more vile person” (ESJ. Vol. 3. pp. 43-44).

It would be cruel to evaluate Yesenin the same way he assessed himself. Such self-esteem was most likely caused by the torments of a naturally sensitive conscience, accustomed to purification by confession and suddenly deprived of this purification (it is natural to assume that, having become closer to revolutionary circles, Yesenin abandoned those few skills of piety that were instilled in him in childhood). And the fact that his soul required prayer and purification is evidenced by verses from the same period:

I will go to Skufia as a humble monk

Or a blond tramp -

Where it pours across the plains

Birch milk.

I want to measure the ends of the earth,

Trusting a ghostly star,

And believe in the happiness of your neighbor

In the ringing rye furrow.

Dawn with the hand of dewy coolness

Knocks down the apples of dawn.

Raking hay in the meadows,

The mowers sing me songs.

Looking beyond the rings of the spinning spinners,

I'm talking to myself:

Happy is he who has decorated his life

With a tramp stick and a bag.

Happy is he who is miserable in joy,

Living without friend and enemy,

Will pass along a country road,

Praying on the haystacks and haystacks.

Sometimes his portrait can say a lot about a person. Yesenin’s portraits speak for themselves: unfeigned purity shines in his face. Such a look cannot be portrayed by a spoiled person. It must be said that some kind of inner openness remained in him until the end, having survived all his falls. But the path he took was a dead end: instead of purification by confession - painful self-criticism, instead of humility - loss of self-respect, instead of following the voice of conscience, the voice of his own heart, kind and loving, - the desire to adapt to the tastes of people - very different - into whose midst he wanted to enter.

Meanwhile, Yesenin’s external biography does not reveal any failures or setbacks that could be the cause of his state of crisis. On the contrary, his life is more than successful. In the fall of 1913, he entered the historical and philosophical department of the People's University named after A. L. Shanyavsky, and at the beginning of the next year, 1914, he began to publish regularly. His first published poem was the textbook “Birch”:

White birch

Below my window

Covered with snow

Like silver...

Yesenin quickly finds his main theme - the theme of Russia, the earthly homeland, loved as if it were heavenly, eternal.

Goy, Rus', my dear,

The huts are in the robes of the image...

No end in sight -

Only blue sucks his eyes.

Like a visiting pilgrim,

I'm looking at your fields.

And at the low outskirts

The poplars are dying loudly.

Smells like apple and honey

Through the churches, your meek Savior.

And it buzzes behind the bush

There is a merry dance in the meadows.

I'll run along the crumpled stitch

Free green forests,

Towards me, like earrings,

A girl's laughter will ring out.

If the holy army shouts:

“Throw away Rus', live in paradise!”

I will say: “There is no need for heaven,

Give me my homeland."

V. F. Khodasevich wrote about the peculiarities of this Yesenin’s Rus': “At the heart of early Yesenin’s poetry is love for the native land. It is to the native peasant land, and not to Russia with its cities, plants, factories, universities and theater, with political and social life. In essence, he did not know Russia in the sense that we understand it. For him, his homeland is his village and those fields and forests in which it is lost” (Khodasevich V.F. Yesenin. - ESJ. T. 4. P. 189).

The young poet’s verbal skill is also growing rapidly: already at the end of 1914, he takes on such a complex piece of language as “Martha the Posadnitsa.”

Not the sister of the month from the dark swamp

In pearls, she threw the kokoshnik into the sky, -

Oh, how Martha came out of the gate,

She took the black writing out of the barrel.

The bell at the meeting split with tongues,

The vigilantes waved their lace panels;

The angels heard the voice of man,

They quickly opened the shuttered windows...

It's hard to believe that the author of Marfa Posadnitsa is only 19 years old. This short poem was a kind of response to the outbreak of the First World War. Having written it, Yesenin greatly pleased the opposition-minded intelligentsia: Gorky himself soon wanted to publish the poem in his journal Chronicle, but the censorship did not let it through: the parallel between the “Tsar of Moscow” praying to Beelzebub and the modern monarchical power was too transparent, and In addition, the poem contained unequivocal calls for uprising:

...And now four hundred years have passed.

Isn't it time for us guys to come to our senses,

Fulfill Saint Marfin's commandment:

Drown out the Moscow noise with daring.

Let's go, fighters, to catch gyrfalcons,

Let's send the wildwash with the need to the king:

So that the king gives us an answer in that battle.

So that it does not obscure the Novograd dawn...

By this time, Yesenin had already left work and study and was engaged exclusively in creativity. His triumphant entry into literary circles was, for many reasons, predetermined.

APPEARANCE IN ST. PETERSBURG

Yesenin appeared in St. Petersburg on March 9, 1915. The first person he visited in St. Petersburg was - no more, no less - Blok, who in those years had already received recognition as the first poet of Russia. In order to begin acquaintance with the literary environment in this way, one had to have considerable self-confidence. The visit was a success. Blok, as a typical intellectual, who in his own breaking conscience was looking for the source of the coveted purity, and, according to the traditions of the Russian democratic intelligentsia, believed to find it among the common people, became interested in the young man who came to him, gave him letters of recommendation, and Yesenin’s path to literary circles was open.

Researchers have repeatedly noted the breadth of his acquaintances. Already on his first visit to St. Petersburg, he met - in addition to Blok - Gorodetsky, Klyuev, Remizov, Sologub, Akhmatova, Gorky, Merezhkovsky and a number of other people, less known today, but no less influential at that time. The fact that many of his new acquaintances were antipodes, incompatible within the same circle, did not bother him. Many of them subsequently talked about their first impressions of the new peasant poet. Everyone agreed that at the beginning he was a very modest young man who did not allow himself any daring antics.

“He seemed to me to be a boy of fifteen to seventeen years old,” Gorky recalled. “Curly-haired and fair-haired, in a blue shirt, an undershirt and boots with a set, he was very reminiscent of the sugary postcards of Samokish-Sudkovskaya, who depicted the boyar children all with the same face.<…>Yesenin gave me a dim impression of a modest and somewhat confused boy, who himself feels that there is no place for him in huge St. Petersburg” (Gorky M. Sergei Yesenin - VE. T. 2. P. 5).

The impressions of Zinaida Gippius are very interesting: “He is 18 years old. Strong, of average height. He sits over a glass of tea a little like a peasant, stooping. The face is ordinary, rather pleasant; low-browed, with a “piggy” nose, and Mongolian eyes that are slightly squinting. His hair is blond, cut in a country style, and he is still dressed in his “traveling” suit; blue blouse, not a jacket - but a “spinjak”, high boots.<…>He behaved with modesty, read poetry when asked - willingly, but not a lot, not intrusively, three or four poems. They were not bad, although they still had a strong Klyuev touch, and we praised them in moderation.

It was as if this measure seemed insufficient to him. You probably already had a secret thought about your “unusuality”: these people, they say, don’t know yet, well, we’ll show them<…>In young Yesenin there was still a lot of manly-childishness and undeveloped prowess - also childish” (Gippius Z.N. The Fate of the Yesenins. - ECJ. T. 4. P. 101).

After reading the poems, Yesenin still sang ditties. “And I must say, it was good. The chanting and sometimes absurd, and even absurdly sarcastic, words were amazing for this guy in a “spinjak” who stood in front of us, in the corner, under a whole wall of dark-bound books. The books, let’s say, remained alien to him and the ditties; but the ditties, with their kind of immeasurable and short, rough prowess, and the guy in the box shirt screaming them, decisively merged into one. Strange harmony" (Ibid.). And then Gippius adds a paradoxical, but in the case of Yesenin, a completely justified thought: “When I say “prowess”, I don’t want to say “strength.” Russian prowess is often great Russian impotence” (Ibid.).

Against the background of general admiration for the dissonance, the opinion of Fyodor Sologub was heard (in writing, however, not recorded by him): “I take this Ryazan calf right by the ear and into the sun. I thoroughly felt his false velvet skin and discovered the real essence under the skin: hellish conceit and the desire to become famous at all costs” (Ivanov G.V. Yesenin. - EZhS. T. 4 P. 142).

If we compare Sologub’s review with Yesenin’s own epistolary confessions, it is clear that his insights are not without foundation. In this appearance to the St. Petersburg public in a hoodie, high boots and a “spinzhak” on Yesenin’s part, there was, in fact, a certain amount of slyness. He presented himself as a pastoral “untouched by civilization” boy from the village, while he was only slightly less familiar with civilization than most of his listeners. Firstly, he had seven classes of education behind him - almost a gymnasium, just without languages; secondly, he had already lived in Moscow for three years, and moved in a quite intelligent environment. But it is clear that appearing before the capital’s snobs as a “child of nature” meant attracting increased attention to oneself and insuring oneself in case of overly picky criticism. If you believe the memoirs of A. Mariengof, Yesenin himself later admitted that he had played a prank on his first St. Petersburg listeners: “You know, I have never in my life worn such red boots, or such a tattered undershirt, as I appeared before them. I told them that I was going to Riga to roll barrels. There’s nothing to eat, they say. And in St. Petersburg for a day or two, until my batch of loaders is selected. And what kind of barrels there are - I came to St. Petersburg for world fame, for a bronze monument" (A. Mariengof. Memoirs of Yesenin. - ECJ. P. 215).

This generally innocent slyness cost him dearly: as a person relates to the world, so the world turns to him. He came to the capital as a “lubok boy” - is it any wonder that the capital, in turn, revealed to him not its true, but its imaginary, “lubok” values?

“During three, three and a half years of living in St. Petersburg, Yesenin became a famous poet,” recalled Georgy Ivanov. “He was surrounded by fans and friends, many of the features that Sologub was the first to feel under his “velvet skin” came out. He became cocky, self-confident, boastful. But strangely, the skin remained. Naivety, gullibility, a kind of childish tenderness coexisted in Yesenin next to mischief, close to hooliganism, conceit, not far from arrogance. There was some special charm in these contradictions. And Yesenin was loved. Yesenin was forgiven for many things that would not have been forgiven for another. Yesenin was pampered, especially in left-liberal literary circles” (Ivanov G.V. Yesenin. - EZhS. T. 4 P. 142-143).

Indeed, if there was something you didn’t like about Yesenin, there was someone else who was to blame for his sins. Thus, the poet Nikolai Klyuev was to blame for his “popular” guise, although his meeting with Yesenin took place, in any case, later than Yesenin’s acquaintance with the Merezhkovskys.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

SOURCE OF INFORMATION AND PHOTO:

Team Nomads

Yesenin S. A. Complete works. M. 1999.

http://www.esenin.ru

http://russian-church.ru/viewpage.php?cat=ryazan&page=82

http://www.museum-esenin.ru/aboutmuseum/museumhistory

Mikhailovsky E. V., Ilyenko I. V. Ryazan. Artistic monuments of the XII-XIX centuries. - M.: Art, 1969. - 240 p. — (Series “Architectural and artistic monuments of cities of the USSR”).

Wagner G.K., Chugunov S.V. Along the Oka from Kolomna to Murom. - M., 1980. - P. 184.

http://history-ryazan.ru/node/

Wikipedia website.